Stories are important. Really important. There is a very real way in which we are made of stories. A friend of mine recently blogged here about the ‘deep self’ as opposed to the ‘higher self’ and this ‘deep self’ is, I believe, made of stories. One of the things (there are so many) that grieves me about modern society is the extent to which we relegate storytelling to the realm of children. Stories, and more importantly story telling, are not just for children. Films can be enjoyable or engaging and books are treasure troves of stories, but there is something primal and vital about storytelling as live performance that we are in grave danger of loosing as anything other than a children’s diversion, and that would be a tragedy. One of my personal soapboxes is that in this country we do not, routinely, teach our children about their own stories. (You seriously don’t want to hear me get started on this!) Let me be clear, at this point, that by ‘our stories’ I mean the stories of all the many different peoples, cultures and traditions that have made these islands their home. One of the best ways for different religions and cultures to learn about each other is for us to learn each others’ stories. However, many people raised in Britain are unaware that there is a long, rich and deep legacy of stories connected with this land. Arthur, the Mabinogi, Beowulf, Robin Hood, the Gododdin, the list goes on. This is our cultural currency and language and we are robbing our children of it. This is a huge mistake and one we seriously need to address.

Both OBOD and the BDO place great emphasis on the story of Taliesin, using it as a metaphor for individual spiritual development and transformation. In many ways it is treated as being analogous to the journey of the Fool in the tarot, who is eventually transformed into the Mage. I have no doubt that the story has great significance to many Druids, of all persuasions, and to many other folk, but despite my deep and abiding love of the stories of these islands, I have a confession to make: I have never really got along with this story. There, I said it! This is not one of my favourite stories and I have always found it problematic.

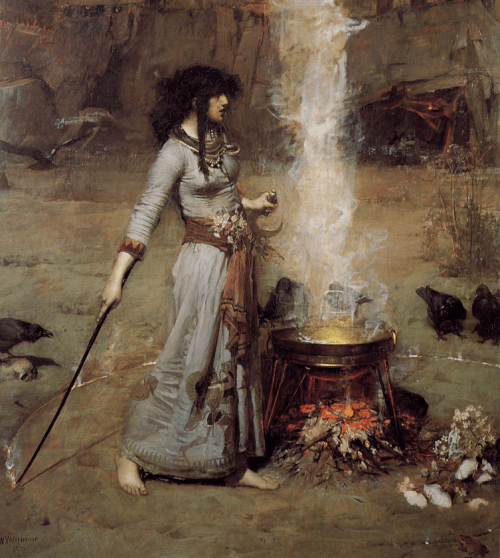

For those that may not be familiar with it the story, in a nutshell, goes like this. Ceridwen, whose name (“Bent White One’) may be a reference to the crescent moon, has two children. One is beautiful, but the other, Afagddu was so ugly that no-one could bear to look at him. As a way of compensating for this, Ceridwen prepares a magical potion in a cauldron that would give all wisdom and the gift of poetic inspiration (‘Awen’) to Afagddu when he drank it. The potion needed to simmer for a year and a day and so Ceridwen hires a blind hermit called Morda, and his young apprentice, Gwion Bach to tend it. With an inevitability familiar to all those used to folklore, the cauldron spits onto Gwion’s hand as he stirs, he puts his hand to his mouth to sooth the burn and the cauldron shatters, since its gift can be given to only one. Gwion becomes the recipient of the inspiration. Not surprisingly, Ceridwen is furious when she realises what has happened and sets out to destroy Gwion. There follows a series of shape shifting where Gwion turns into various creatures to elude Ceridwen and she in turn becomes the appropriate predator. Eventually Gwion turns himself into a grain of wheat and Ceridwen, as a hen, swallows him. This action leads to her becoming pregnant and nine months later she gives birth to Taliesin, ‘Shining Brow’. Ceridwen finds herself unable to kill the baby and instead sets him in a leather bag in the water. The bag was found by the noble Elffin ap Gwyddno, who raised the child. Taliesin became a legendary poet and was renowned for his great wisdom.

For most, this is read as a tale of initiation through the elements and the through the womb of the goddess to become an almost superhuman being, and one possessed of what might be called ‘Enlightenment’.

As a child (I first read the Mabinogi when I was about 10, having seen a set of Welsh Mystery plays about it on television) I struggled with this story because it seemed deeply unfair to me. It was not Gwion’s fault that he tasted the potion in the cauldron, but it was extremely unfair that Ceridwen spent so much time and effort on it out of love for her son (who had been dealt a raw deal in the first place) only to see her plans shattered. With mature reflection, this is the key way in which the story speaks to me. We can plan and prepare as much as we like, but at the end of the day life is not fundamentally fair and inspiration strikes where it wishes. This connects, to my way of thinking at least, to the Germanic concept of wyrd shown in the poem Deor and to a lesser extent Beowulf and the Dream of the Rood. The world is not fair, or good, it is fundamentally neutral and uncaring. Sometimes the odds are stacked against us. In Irish stories, heroes are often placed from birth under a geis or gaes that forbids them from a particular action. In several of these stories, the hero knows his death is at hand when he is placed in a situation where he has no choice but to break one of these injunctions. Cuchulainn, for example, is under gaesa that he must never refuse hospitality and he must never eat dog meat. When he is met on the way to battle by an old woman who offers him dog meat to eat he knows that his time is near. In the end, we all lose….but we can choose how we lose and that’s important. We can be overwhelmed by the unfairness and suffering in the world or we can take a stand against it even if we know we can’t win. True heroism (a virtue we make too little of these days in my opinion) is to fight a battle you cannot win because it is the right thing to do. This is the lesson I learnt from To Kill a Mocking Bird at school (I loved that book) and again, recently, from, of all places, Dr Who (‘Goodness is not goodness that seeks advantage. Good is good in the final hour, in the deepest pit, without hope, without witness, without reward.’) This view of heroism, to do what is right when there is no hope seems to me to be totally entrenched in the Germanic and ‘Celtic’ worldview. So much so that I cannot help wondering if Ceridwen (a goddess, after all) knew what the final outcome would be before she began? At any rate, she does what we must all do and starts from where she finds herself (as my mother would say, ‘it is what it is’) and participates in the transformation of Taliesin. We constantly find ourselves in situations that are not ideal; not what we would have chosen, and yet we make the best of them that we can. We are good people, hopeful people, joyful people not because we have failed to understand the depths of suffering and despair in the world, because we understand it, and we choose to be those things anyway.

Perhaps that is the truest lesson of Ceridwen.

Leave a reply to lornasmithers Cancel reply